Lothar Mentel, CEO and chief investment officer at Tatton, explains why capital expenditure is an important part of any dynamic economy.

Throughout this year’s recovery, consumption and household spending have been key factors to watch. Global growth can only continue if consumers are confident in their prospects – which is why we have been closely monitoring developments in employment and household savings rates. This is particularly important in the face of wavering economic sentiment and the likelihood of a difficult winter ahead.

Equally important is investment in the post-pandemic future. So far, governments have looked like the main architects of that investment drive. President Biden is planning a wave of infrastructure catch-up spending in the US, while British and European politicians are exploring similar measures with a focus on green infrastructure. Fiscal policy taking the initiative here makes sense. The combination of high private savings levels and historically low interest rates put governments in a good position to spark growth through public spending, while the cost of such investment remains low for the foreseeable future.

For a stable and sustained recovery, though, productive investment will need to come from the private sector too. Economic activity needs new technologies and avenues of production (particularly in the face of the daunting environmental challenges) and public spending can only go so far in providing it. When businesses focus on capital expenditure (capex), it is a sign that growth is self-sustaining. This is vital for ensuring a broad-based recovery – avoiding overreliance on consumer confidence or individual sectors.

Capex also indicates that businesses are confident about the future. There is little point investing in new products unless you think people will be able to buy them. So, if we see strong capex spending it follows that corporates are confident about the economic recovery. This is particularly important now, considering how the pandemic experience has altered perceptions of productivity and technology across society – from online infrastructure to the green transition.

Corporate investment will also have a big impact on inflation and the labour market. Capex can sometimes be seen as a proxy for productivity growth – as businesses look for improvements to save on costs. For example, rising wages and a tight labour market might prompt a business to automate its production line and cut jobs – thereby pushing up unemployment while increasing productivity.

The relationship between capex, productivity and labour is particularly relevant right now. The financial pages have been filled with talk of ‘stagflation’ this week – the phenomenon of rapid inflation at the same time as slowing growth and rising unemployment. Given that unemployment tends to counteract inflation, and vice versa, this can usually only happen with a significant supply-side shock. The 1970s oil shock was a prime example of this, and newspapers have been quick to draw comparisons between then and Britain’s current heating gas shortage.

We agree with most economists that this comparison is a little far-fetched. Short-term supply issues can bump up prices, but longer-term trends are usually dictated by demand, unless there are structural supply constraints (such as the oil cartel controlled by OPEC). Otherwise, we should expect rising prices to incentivise more capex, eventually pushing up productivity and keeping a lid on spiralling prices.

The positive part of this story is that productivity growth is the main driver of sustained real (inflation-adjusted) economic growth – lifting corporate earnings and (in their wake) investment returns as well as living standards. That is the theory, at least. In practice, displaced labour can cause big problems, as workers’ skillsets effectively become stranded assets, requiring further investment in retraining.

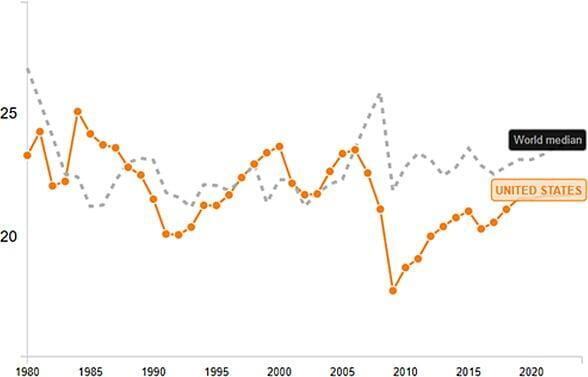

Source: Worldbank, IMF

Still, capex is an important part of any dynamic economy. In fact, capex – or the lack thereof – was one of the main disappointments of the decade after the global financial crisis (GFC). The chart above shows US and global capex as a percentage of GDP. Corporate investment took a big hit following the financial crash, and has been tepid ever since. This has gone hand-in-hand with a post-GFC slowing of productivity, and a relatively stagnant global economy.

Fortunately, last year’s recession has not shown the same capex drop-off. Projected corporate investment for 2020 is broadly in line with the year before, and the expected 2021 figures already show a pick-up. This has been matched by the rapid US recovery earlier this year. Even though other growth indicators have wobbled recently, should investment stay at a decent level, it bodes well for the future.

There is perhaps a worry that capex spending has been quite unbalanced. Most of the capex recovery has gone into information technology (IT), while other sectors have seen their corporate investment levels fall. Optimists would say IT investment is the most needed – particularly for the so-called green revolution ahead. As written before though, new technologies still need more materials and old-fashioned infrastructure to work. Fortunately, governments seem eager to provide on the infrastructure side.

As such, the outlook is mostly positive, even though capex intentions have dropped off recently. Companies flush with cash – like the US mega-tech sector – can fund spending out of their reserves, or have access to raising funds at low yields in capital markets. Others must resort to bank loans. The outlook for those companies is unfortunately less positive, with bank loans not recovering as much since early 2020.

The main risk to the overall picture is what the current supply shock might mean for investment intentions. As noted, the energy crisis and widespread supply bottlenecks this year are mostly one-off affairs, unlikely to cause elevated inflation over the longer-term. Short-term price shocks can still have a big impact on confidence, though. Should price issues eat too much into corporate profit margins, it will make companies less likely to invest – weighing down on future growth prospects. For now, companies seem to be absorbing the costs, but this is something we will be keeping a close eye on.

By Lothar Mentel, CEO and chief investment officer

By Lothar Mentel, CEO and chief investment officer

Lothar co-founded Tatton in 2012, and has overseen its growth to becoming a leading discretionary fund manager in the UK. Lothar has previously grown award-winning multi-manager funds and was previously Chief Investment Officer at Octopus Investments.

In an investment management career spanning three decades, Lothar designed and launched the Barclays Multi-Manager fund range and held senior roles at NM Rothschild, Threadneedle and Commerzbank Asset Management.

Educated in Germany, Lothar holds a postgraduate degree in Business and Economics (Diplom Oekonom) from Ruhr-Universitaet Bochum and is a regular contributor to international conferences, publications, and symposia.